Shards

A guest blog by Aini Butt.

You seek validation from the mirror,

a forced smile to please its reflection.

Your tears blurring your vision,

a forceful flood thirsting for its affection.

You work tirelessly, pushing all your doubts and fears aside, towards that romanticised image – the perfect depiction of success and happiness. When you pause to reflect, whether that is by choice or a grinding halt forced upon you, holding your breath before you open your eyes and gaze upon your reflection in the mirror. It's not what you had expected...

You see yourself as a failure when your mirror doesn't show what you had envisaged. You close your eyes. As you open them again, you look at the mirror hoping that the forced smile will somehow make it all better. But you forget, that it is not a mirror's job to entertain your desires; its reflection does not lie – and it will not lie to please you.

These are the struggles that we face when we have developed the ability to reflect, but the years of trauma do not allow us to practise self-compassion and accept our true reflection. Whether it be the result of generational curses, societal standards, toxic relationships, we hold ourselves and our image at ransom against unrealistic expectations.

One of these unattainable standards has been perfectionism, which I'm unlearning through my art. I have been trying different art media for a while now and have had some that turned out a lot better than expected. Despite the harsh criticism from within, they were seen as good enough attempts and deemed worthy of sharing with others.

These are the leftovers of an art piece I was working on. I tried something new and it didn't work out; not being able to face this failure during an already difficult time, I didn't have to think twice and it ended up in the bin.

Sat there at my desk still struggling to write in my journal, it dawned on me that I was still trying to escape those things that hadn't gone to plan. In the process of this desire to discard any evidence of my failures, I was trying to escape the lessons. Maybe because I'm tired of the lessons and the hurt that comes with them – every time!

I took the art out of the bin and tried to rip it up. Yes, it was anger and frustration, but allowing this emotion to flow through my body was the only thing that was within my control, even if for a moment it seemed like I was losing it. When I realised that I couldn't rip the Yupo paper, tears of frustration rolled down my cheeks. I grabbed the scissors and started cutting into the already-ruined art piece. When I had finally cut it into several pieces, I closed my eyes and sunk back into my chair. Looking at the pieces lying in front of me, the desk light shone its light on one of the smaller ones; the metallic gold shimmered, maybe even more so than when it was part of the whole picture.

All I could see was the glistening beauty of that small piece, which was part of my failure. In that moment, I forgot that I had failed to depict the image I'd had in my mind. I knew that going back to the same image was now impossible after cutting it into pieces. Even with the best efforts, I would not be able to recreate alcohol ink design in an identical way. I stuck the pieces into my journal and filled the gaps with gold foil.

Is that what we are meant to do when life breaks us apart and that desired reflection in the mirror is shattered into smithereens?

Sometimes we need to accept that the image we were working towards has been destroyed and it is only when we practise self-love and self-compassion that we will be able to see the glistening beauty of our shards.

My Response to the Plan

A guest blog by Abigail Gray.

The day before the new SEND Improvement plan was published, I was at the Outstanding Schools Conference at County Hall with leaders of international schools. There were delegates there from all over the world: India, Ukraine, Greece, The Netherlands, France, Dubai and, of course, the UK.

My good friend Louise Dawson, a passionate advocate for inclusion and an international SEND consultant, had invited me to her session on putting SEND policy into practice. It involved a hilarious pass the parcel activity, but typical of a great SEND practitioner, there was deep intent in the fun. There were presents but also questions instead of forfeits. School leaders quickly began an animated conversation about the challenge and opportunity of an inclusive school. What are the things we need to change? What needs are hardest to meet in the classroom? How do we fund effective support? What is included in our universal offer? How do we meet and manage expectations? This list went on.

One of the words that Louise used repeatedly in her presentation was ‘intentional’. She made it clear that inclusion doesn’t happen by accident, it happens by design. I think she’s completely spot on.

It’s long been my observation that no new plan, no law, no regulation, guidance or policy enacts itself. Writing it down doesn’t make it so. It takes people to do that.

It takes people to firstly be aware of what it is that they need to do, then work out how it might best be done. It takes action and courage and stamina and commitment. It takes personal and professional integrity. Every head teacher, every local authority officer, every teaching assistant, every teacher, every educational psychologist, every one that makes it happen. All of us.

All this talk of transformational plans, while the transformation yet to take place in education is the one that genuinely places children with SEND at the heart of what we do. At the heart of our inspection frameworks, our performance measures, our planning, our pay spine, our conscience. Not only do we need to be absolutely clear in understanding our obligations but, as Louise rightly says, of our intentions.

It’s always very clear to me when this has happened in a school. When a school gets it right for children with SEND, everybody benefits.

There is a sense of ownership and pride in the relationships that exist with families and children.

There is an understanding of the law and its importance in protecting the rights of the most vulnerable.

There is a willingness to listen to all feedback.

There are opportunities to try and sometimes to fail in pursuit of something better.

There is a shared belief that all children can achieve and thrive at school.

There’s a transparent approach to funding for SEND and to establishing value for money.

There is realism in recognising the limitations of both people and resources.

There is a genuine interest in staff well-being and development.

The graduated approach, we hear so much about for students, is in place for us and our own systems.

There is collaboration.

There is laughter.

There is success.

I know. I’ve been there and it was great.

A Day in the Life of a Happy Vice Principal

A guest blog by Madeleine Fresko-Brown.

There’s a lot of negativity in discourse around education at the moment. Times are tough, and it can be hard to work in a system you know is not working well for every child or every adult involved. But it is possible to be happy in this job!

Just in case anyone was doubting, it is possible to work in a comprehensive secondary school in the UK in 2022 and be really happy 😊 #edutwitter @thosethatcan

— Madeleine X F-B (@M_X_F) November 1, 2022

I’m a new vice principal of a large, busy inner London secondary academy. Here are some of the things which give me satisfaction, fulfilment, and yes, happiness at work.

1. Walking into my school and taking in the excellent student art adorning the walls and the high spaces. Our art department scored in the top 1% in the country for the UAL extended diploma, and you can see why! I brought my family (both my parents and my children) to the art show because I wanted to show it off – not that it had anything to do with me at all. But how lucky am I to work in a place like this?

2. Morning gate duty. Seeing the faces of our year 7 & 8s in the morning, saying good morning with a smile, them politely saying good morning back. It’s always good to be able to connect with some of the ‘trickier’ students in a positive way first thing, before anything has gone wrong

3. Line management meetings. Perhaps some groan at the prospect of these, but I really enjoy them! I meet with the principal (my line manager) and everyone I line manage weekly. It takes up a lot of time (2 almost full days of my timetable devoted to this) but it’s worth it. Having a good chunk of time with the principal means I can always run ideas by her, get her wisdom and the longer view of her experience of the school, as I am still quite new. Each person I line manage comes prepared with questions and things to discuss – sometimes small, sometimes big. As a teacher I am by nature interested in people’s development, be they adults or children, and I consider it a privilege to be part of my colleagues’ journeys as they work out how to do their jobs to the best of their ability, and reflect thoughtfully when things don’t quite go their way. Now I’m a Vice Principal, I am managing more senior colleagues (3 assistant principles, the SENDCO, and a Curriculum Area Lead) as well as meeting the DEI (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion) lead and Induction Tutor on a regular basis. As each of these people bring a wealth of experience to their roles, I always feel I have plenty to learn from them while coaching them to achieve their visions. This makes me happy.

4. Teaching! We tend to get less and less time in the classroom as we progress through senior leadership, which is necessary but can be sad. I very much enjoy the classroom time I do get- this year with year 11 and year 13. I always find the connection I have with pupils in my own classroom feels so much stronger than with pupils I only interact with on corridors. Once I’ve taught a child, even if only for a few weeks, I feel I ‘know’ them and they know me.

5. Learning walks/observations/lesson walkabouts. As a ‘teaching & learning’ person, I love popping into lessons the most. I wish I found more time for it but I make sure I do it informally once a week and offer positive praise on a postcard. I even popped into some senior colleagues this week who seemed to quite like receiving a postcard themselves! Longer, more formal observations are also really enjoyable, as are the feedback conversations afterwards where colleagues show a genuine desire to reflect and improve.

6. Coaching. Every teacher in this school has a period allocated for coaching, and every member of support staff also has peer coaching as part of their CPD programme. It’s pretty amazing. I am paired with the other VP for coaching and it’s a great space to be able to come together and listen to each other. We’ve been trained on a couple of models and we don’t always manage to stick to them religiously, but the space is there and we both know it’s for listening, probing, and developing, which at different points has helped us both a lot. We also adopt a coaching approach in our line management meetings, which avoids the feeling of coming out of a meeting feeling like you’ve been told what to do.

7. Weekly Teaching & Learning meeting with middle leaders. Every week the senior leaders responsible for teaching & learning, curriculum directors and curriculum area leaders (CALS) meet to discuss our priorities, progress, next steps, feedback and more. I enjoy chairing these meetings. The directors and CALS are a thoughtful and honest bunch, and help keep the senior team in check, lest we suggest something that has been tried and failed before, or would be an unreasonable workload burden. As well as giving us valuable feedback, I hope the middle leaders feel that the meetings help them to develop, both in their understanding of whole school considerations, and in thinking through strategy for their own departments in collaboration with others.

8. I love leading CPD, facilitating others to lead, and the feedback from colleagues. At a recent short CPD session entitled ‘every minute counts,’ I invited several colleagues to share tips for saving minutes in a lesson. Suggestions included using stopwatches on the board, carefully numbering books and chairs and handing them out in a perfect order, the importance of a teacher being silent during the silent Do Now, modelling using a visualiser, mini whiteboard AfL, and more. I gained happiness from seeing how thoughtful and effective my colleagues are when they really think about their practice. Leading DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) CPD on LGBTQ+ inclusion with a colleague was also a very memorable moment from which I came out buzzing. One colleague bravely shared his experiences of transitioning, and everyone engaged so thoughtfully with scripts we had prepared on how to respond to certain comments/situations.

9. I like the structure and routines of our leadership meetings: we have a ‘rolling chair’ so each member of the team has the experience of chairing (mainly preparing the agenda, timekeeping and the important role of bringing snacks!) We always start with an ‘opening round’ of something positive from our week – often bringing lots of shout outs for colleagues, and ‘something educational’ where the chair brings something for us to read/watch/discuss and learn from. I appreciate that we prioritise continual professional development for our team through this routine. My colleague and I also deliver extra DEI training to the SLT on a regular basis, which is a rewarding and enjoyable experience.

10. Going home. Yes I love my job and I also love leaving it at the end of a day! On Mondays, I prioritise my physical and mental wellbeing by going to yoga (in school as part of the wellbeing offer) and then a gym class. On Tuesdays I leave late because of leadership meetings (finishing at 6.15. At my first school, SLT would regularly be in school until 7.30pm and later). Other days I leave at a reasonable time and take my 2 kids to their swimming lesson or pick them up from after school club. Evenings I’ll often work, and often until quite late (10.30pm is not unusual) but given I only start this after the kids are in bed and I’ve eaten, this doesn’t feel unreasonable. I get my most productive work (and almost all my lesson planning) done in the evening as there are fewer interruptions. Although I do need to work most evenings, I won’t turn down a social arrangement if the opportunity arises. Last week I went to dinner with a friend and next week I’m going to the theatre. The work will get done at some point!

That concludes my round up of the things that make up the main chunks of my time as a happy senior leader. I haven’t mentioned small but important things: little conversations, smiles, or sympathetic looks exchanged with colleagues, which remind me that we’re in this together and working towards the same goal. The way a year team leader or assistant year team leader will step in to help if I’m struggling to get through to a student. Getting to know support staff, some of whom have been at the school for over 20 years and really seen it all! Interviewing year 6 students joining us next year, or year 8 students selecting their options, meeting parents and carers at parents’ evening and open evening. Seeing SEND students looking after the two chickens we adopted, reading the school newsletter and attempting to process the vast number of things that happen in this institution, watching the students play a sports match (I haven’t done enough of this yet). Welcoming year 5 and 6 students for science workshops, arts days, sports events, watching the school production, the staff panto, the student band who practise in a science lab with their trombone, trumpet and flute! I could go on.

As for challenges? Yes they exist. My school has been through some major tragedies and should one of these occur while I’m in post, no doubt it will be an incredibly difficult time. But when it comes to smaller, ‘everyday’ challenges, much of happiness comes down to mindset and I find myself in a mindset where a challenge is a learning opportunity, not something to stress over. There are never enough hours in the day, no matter what your position in a school. I prioritise things that affect other people (colleagues, students, parents) and things I know I will be held accountable for. At times I wish I was doing more, but I know my limits and know that sustainability is important for me and my colleagues.

Above all, knowing I’m in a place with people who have the same goals as me – to do the very best for the young people in our care, to help them make the best progress they can and secure sparkling futures – is what makes the difference, and what keeps me smiling (almost) every day.

Holding Your Breath Until Wednesday Lunchtime

A guest blog by a headteacher who wishes to remain anonymous.

As a school leader I read lots of tweets and talk to lots of colleagues about the immense stress we are under whilst waiting for Wednesday lunchtime when your school is in the OFSTED window. Some of the tweets are very amusing and you can relate to them and have a chuckle and it is true that you can hear a collective sigh of relief run through my school at around 2pm on a Wednesday when we all realise we are safe for another week. However, the reality for many of us is very worrying.

I have been a Head Teacher for 12 years, I am no ‘inspection virgin’ and I can hold my own in a professional dialogue about my school and our context. I haven’t always felt this absolute dread at the thought of anyone coming in to judge our learning – in fact I used to look forward to it as an opportunity to show what we are doing and to learn some improvement strategies. Sadly, I am not even sure that I can pinpoint the exact moment this started to change for myself and colleague heads. The latest OFSTED framework, when it was published, was my favourite (I realise how sad it is to admit that you have a favourite framework!). I have always been enormously proud of the fact that we did not narrow our curriculum, that we offered a broad and balanced diet for all our children, even our year 6 pupils. We have always been focused on health and well-being, we run forest schools on site 3-4 times a week, we have a wonderful school dog, and ELSA room that is used every day for a wide range of children. We achieved a good inspection 5 years ago and until recently I honestly believed that our school is better now than it was then.

SO WHAT THE HELL HAS CHANGED?

The region where I work has just been named as the lowest achieving local authority in the country for GCSEs and A-Levels; I suspect our Key Stage 2 results are about to say the same thing. As a school leader I know that this is not good enough and something needs to change. However, we also have the highest number of SEND pupils per LA, yet we have the lowest specialist provision. We have huge numbers of children in mainstream schools that are being failed though a lack of resources. Everyone I know who works in education in this area is working to capacity – we can do no more. However, the inspections that have taken place in this authority in recent weeks in ‘good’ schools have been described as brutal by staff and governors that were involved. It seems that OFSTED would like us all to teach to a preferred phonic scheme with a preferred teaching style and every curriculum subject should be taught through a ‘bought in’ scheme, where your poor subject leaders (who probably get half a day a term if they are lucky) are expected to know what the progression and skills look like from age 4 to 11. In all of the negative feedback that heads have shared with me, the most disheartening thing is that there was no professional dialogue – staff were stopped in their tracks when talking about their provision. There were no opportunities to provide more evidence on the second day of the inspection – decisions were made very quickly and the inspectors were ‘not for turning’. This is very different to both inspections I have undergone as a leader – one that judged us as RI and the second one as good. I am worried this new ‘brutal’ system is the new inspection framework and in a world where Head Teachers are not staying in post beyond 5 years, and teacher recruitment is at an all-time low, how are we ever going to make a difference in children’s lives?

For some time I have known the system is broken – yet often speak about the joys of school leadership - and so now I feel like a hypocrite! But it has to be said and to a wider audience than our Chair of Governors when we are having a moment. My blood pressure is currently sitting at 160/106 and my GP has told me to relax! I am of course in school, the time is 11:15 and I am holding my breath!

Image by Freepik

The View Down the Mountain

Here in England, October half term has finally arrived. If you're feeling shellshocked, numb, grumpy, irritable and/or as if you've been run over by a truck, this is not unusual. Like many of us, I remain a stubborn optimist, but there's no escaping the fact that it's been hugely challenging for almost everyone I've met working in schools since September, and I've had the privilege of meeting hundreds of you to talk about wellbeing, working with parents or for coaching.

Today, I'm extracting myself from the sofa (the weather is practically demanding a duvet day) and studiously ignoring the domestic and family to-list to share a powerful wellbeing tip, based on an idea first shared with me by Emma Turner: turn your to-do list into a 'ta-dah!' list - look at what I've achieved!

Rather than looking ahead at everyone and everything else that demands a piece of you; rather than berating yourself for perceived flaws or mistakes; rather than worrying about the next half term ahead or launching straight into the laundry pile or DIY, can I urge you to take a few moments to look back at everything you've achieved since the beginning of September? Many of you will struggle to start with. 'It's just my job!' you will protest. 'I really haven't done much.' (Our professional is notoriously self-deprecating). I don't believe you.

- That trip you finally managed to run? What effect did it have on the child who's struggle with confidence this term?

- That parent who stopped to thank you at pick-up one afternoon? What exactly did they say? What does it mean for their child?

- That colleague you made a cup of tea for because they were looking a bit frazzled? What did that gesture of humanity mean in a stressful week?

- That student who made eye contact and smiled at you for the first time? How much patience, how many subtle skills on your part did it take to get them to that stage?

The challenges you've survived, the resilience you've shown, the laughs (even or especially the darkly inappropriate ones) in the staffroom, the mutual support, the skills you've learned, the progress your pupils have made, the fact that, even in the last week when you may have been on your knees, you still did it - you still smiled, you still taught, even as the leadership of our country imploded...

Take a moment to give yourself a pat on the back. Note it down somewhere - in a journal, an audio-file or on a few post-it notes. Treasure it. Because you truly make a difference, ever single day and you deserve, in the words of the legendary Rita Pierson, to find joy and a sense of achievement in the invaluable work you do.

The Reality of Life as a Woman with ADHD

A guest blog by Krystina Cheshire.

I have such a fear of letting people down. Sometimes I feel like I'm seen as a problem by other people because I am different, and I hate that. The reality is I don't think or feel the same, I can’t focus in the same way and what motivates me is different. I lead with my emotions and they dictate what I do. I am different and society doesn't react well to anything that's different. The battles I face every day are also not the same and therefore I feel other people can't relate or don't understand me. In order to understand something, you have to first learn about it to know it. When people don't know about something they tend to judge. Judging leads to criticism and a lack of compassion which can lead to a breakdown in relationships. Positive relationships are fundamental to a happy and healthy life and so a change is needed.

When we hear the term Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD, quite often we find that we imagine a young boy who can not concentrate and is bouncing off the walls, fidgety, forgetful, highly energetic, argumentative and generally just difficult to manage. In the UK between 2% and 5% of school aged children are considered to have ADHD, although the actual figure is thought to be much higher if we think of the children who go undiagnosed. This tends to be the case particularly for girls. This is mainly due to girls exhibiting their ADHD traits differently or being able to mask their symptoms, particularly if they also suffer with anxiety. When the diagnostic criteria was created to assess ADHD they focused on male symptoms, making it harder to be diagnosed as a female and also ignoring certain symptoms which, while prevalent in many individuals with ADHD, are not even on the criteria. Many people don’t realise that ADHD is a life long neurodevelopmental condition. It is something you are born with. It is genetic. There are physical differences in the brain and how it works that cause individuals with ADHD to think, feel, interpret and react to things differently. It is not a choice or something they can control. For many individuals with ADHD, their symptoms become easier to manage and less obvious as they enter adulthood, simply because they have learned to adapt. At this point their symptoms may no longer have a significant impact on how they live their life and it would seem their ADHD has disappeared. However, ADHD statistics UK estimates that between 3% and 4% of adults have ADHD and many of these individuals will not have a formal diagnosis. A rise in awareness and understanding of ADHD has led to an increase in diagnosis, particularly in women. I am one of those women.

I had a good upbringing and was well cared for growing up. As a child I was shy, lacking in confidence and self-esteem, but I loved art and music and anything creative. I did not have many friends and I never really understood why. I was bullied throughout most of my primary and secondary education and experienced a lot of social anxiety. I was so anxious about getting into trouble or disappointing those around me that I often bit my tongue and kept my thoughts to myself while going along with things, especially in school. When I didn’t hold it in or if I spoke my mind, things did not go well for me. I was a people pleaser and wanted to make my parents and teachers proud. As a result, I was no trouble at school. I achieved academically, always did my homework, learned how to manage my time so I was always early for everything out of fear of being late. I would pack, check and double check my school bag to ensure I never forgot anything. I hated being anywhere new or trying anything new. The only criticism I ever got was for not putting my hand up in class and for not believing in myself. I was also constantly apologising for things that were not always my fault or within my control. People would describe me as polite, mature, sensible, responsible, too serious and very sensitive with a tendency to become overwhelmed and stressed. I struggled with emotional regulation and felt every emotion very intensely which caused issues in my relationships and gave me very hard and steep learning curves. I never needed as much attention as those around me, because I was always ‘OK’, and therefore I felt I didn’t get much.

As I entered adulthood I appeared to be doing well. On the outside people would see a woman who was on it, super organised and efficient, helpful and agreeable. You wouldn’t think there was a problem. But inside I suffered deeply with insecurities, anxiety and overthinking. Perfectionism is exhausting. Living my life in fear of how others would perceive me if I failed or didn't live up to their expectations. As a result, I got to my 30s, I seemed to have the perfect life, a husband, a home, two beautiful children who mean everything to me and my career that I am very passionate about. But I was deeply unhappy and I didn't have a clue who I was and what I wanted. I had done the set routine to achieve the standard life goals yet did not feel happy.

I'd spent so long thinking about others, agreeing just to avoid conflict and putting my own wants and needs last that I found my mental and physical health falling apart. As the woman of the house there is an expectation that you've got it all covered. If anyone needs anything they'll ask you where it is and if something isn't done, they'll ask you why you haven't done it or get grumpy or annoyed that it's not been done as if they had no responsibility over it at all. Fulfilling the roles of mother, wife, daughter, teacher is exhausting, especially when you feel that you’ve lost yourself as an individual. My life had become no more than the roles I played. I was living to serve others. I was not living. This intensified my ADHD symptoms to a point where I was no longer coping. As an undiagnosed adult at this point, I had no idea that the struggles I was having were due to my ADHD and so I felt like a failure. Why were other mothers, wives, teachers managing life while I couldn’t. Under the increasing expectations and responsibilities that had become my life I felt like I was falling apart. My memory was being affected, I was getting less sleep, I experienced sudden episodes of anxiety, panic attacks, nightmares and flashbacks. I was becoming more argumentative and confrontational and experienced bouts of depression and would have days where I just couldn’t help myself but cry – yet I couldn’t explain why I was crying. I was so tired and was struggling to get through each day and my relationships broke down.

I had become so used to saying yes that despite the above, it still felt uncomfortable to say no. The few times that I did took a vast amount of courage and was often met with shock, disbelief and caused conflict. As a risk averse person, this is so uncomfortable, so it is easier to just agree or stay quiet. I found myself mentally crumbling under the weight of societal expectations and responsibilities that life has given me. I got through each day but I was just going through the motions.

However, during this time of struggle I did find some relief. After my daughter’s ADHD diagnosis I learned as much as I could about it, the science behind it, how it affected the brain and how it presented and affected females. Through this research I found that I could relate, not just to one or two symptoms, but many. I sought an assessment and after a year of waiting I was diagnosed with ADHD. I was surprised that I met the hyperactive criteria during my assessment, but I learned that hyperactivity can also be hyperactivity of the mind. It does not always present in a physically outward way. People with ADHD, and females in particular can also experience Rejection Sensitivity Dysphoria (RSD) which causes extreme sensitivity to perceived or real rejection or criticism. Suddenly, so many parts of my life made sense and I felt a huge sense of relief. Now, I could start to look at my symptoms and the things I was struggling with through a different lens and the beauty was, now I knew the cause I could find the solutions. Nothing is going to take these symptoms away but I can now apply strategies and a different mindset to help me cope better. Now I know why I experience the things that I do, I don’t feel as anxious to talk about them. Once I started talking about them I felt less weight on my shoulders.

While I have highlighted various challenges I have faced in my life due to my then undiagnosed ADHD symptoms, I do also wish to highlight the many benefits that I would not change. I crave stimulation, otherwise I get bored. This has been a gift in my career as a teacher and is beneficial in many other aspects of my life. The strategies I use to mask and adapt for the benefit of others means I can get on well with a range of personality types in all sorts of situations. I'm curious and seek excitement. I am incredibly passionate about the people I care about and my interests. In these situations I can hyperfocus, maintaining concentration and staying motivated and on tasks for hours and hours without stopping or losing interest. When I am passionate about what I am doing I am unstoppable. I feel emotions intensely and I am attuned to the feelings of others making me incredibly empathetic. My perfectionism means I am always striving to do better and that means I am constantly going through personal growth and self-reflection. My hyperactive mind can be my worst enemy but it is also my biggest strength as I am a problem fixer. My fear of forgetting or messing up means I can become hyper organised. Individuals with ADHD are creative problem solvers, and we are the best people at coming up with strategies on how to best help ourselves and others like us. Quite often, what works for us also works for others. Listen to us. Value us. Respect us. We can offer so much if we are given the space and freedom to work in the way our brains are designed to work.

I am still learning about my own ADHD and how it impacts my life. It will be a lifelong learning experience, but one thing is for sure, I will no longer be quiet or apologetic for who I am. It is time to start being me.

Having It All

A guest blog by Kerry Rice.

Mums can't have it all, yet we continue to try.... to work like we don't have children and parent like we don't have jobs. When I was engrossed in celebratory end of year reports, my son, Cruz, penned a letter wishing for more attention from me. At school, a student criticised me for taking a shortcut when creating a lesson resource - a cheat I wouldn't have used prior to becoming a mum. Yes, I chose to become a working parent but this isn’t the dream I was sold. I love my job and love my son even more but I’d hoped for a throuple, not a love triangle.

Each day I have to decide which balls I'm going to let drop; which plates I'll no longer keep spinning, and hope that I have a big enough broom to sweep the broken pieces away; the shards of self doubt and splinters of shame. 'Mum guilt' isn't an imaginative name but the person who coined the term was probably a working mum saving time by opting for the obvious so they could help their child with their homework.

I know that I’m lucky to have a job which allows me to do 3 out of 5 school pick ups, reducing my childcare costs and enabling me to take Cruz to after school activities. But, despite what is often portrayed, a teacher’s day is not from 8 ‘til 3. So I wake up at 5am to plan and prepare, and mark students’ work on a clipboard interrupted by cries of, “Mummy, you weren’t watching!”

My son's asleep right now. It's the weekend but I want to plan a class trip. Perhaps I should be doing it now before he wakes but then I wouldn't be able to mention 'me'. Always the add-on, as if my needs no longer matter. Apparently taking a shower is self care and reading a book is a treat. When did completing basic tasks become something to celebrate?

I'm not sure how 'having it all' came to be. No longer the dream of dissatisfied housewives, it's the expectation for most. And I am clueless as to how it will change because, despite my rants and tears, I still aspire to be both a perfect parent and excellent educator. I know it's impossible yet I try. I continue on my quest to achieve the unachievable, continue to accept the obstacles and injuries. There's only one major casualty in this mission though...me!

A Tale of Two Ofsteds

An anonymous guest blog.

In the last 12 months I have had the pleasure (not always) of working in two comparable schools within the same local authority. Both schools, of similar size, face challenges based on the area they serve and the deprivation of their cohorts. Similarly, both schools have recently undergone Ofsted inspections and unfortunately on paper they are both graded the same.

It is in this respect that they are not comparable.

One of these schools is still promoting outdated pedagogical practice and using learning walks and book looks to terrorise and intimidate staff. Particularly when the most feedback ever given to a group of books is 'Why haven't you differentiated the task 5 ways in your lessons?'

In addition, practices such as printing out your planning every week to display in your classroom, ensuring your displays are all triple backed, triple marking every single book every day and not once providing CPD in staff meetings and INSETs were just accepted as normal. Teacher mental health and wellbeing was not mentioned and I was once in a situation with a senior leader where it was actively dismissed. All of this before you even start to unpick curriculum design, sequencing and intent. Needless to say, it was thin in all areas and in many non-existent.

In complete contrast, School 2 has invested serious energy and time into teaching and learning with weekly staff development sessions, a coherent and consistent curriculum threaded through with actual evidence and research and clear explanations for decisions being made and followed through. Staff are supported; their time protected and decisions made so that even when expectations are high, workload can still be manageable. The culture at this school is quite frankly, refreshing. People have professional discussions and engage in their practice on a deep level with a focus on achieving high outcomes and experiences for the pupils. Every decision is carefully crafted and has strong fidelity to the core vision and values running through the school. Most notably, staff well being is acknowledged and there is no culture of ‘it’s a tough job, you just have to turn up’.

Don't for a moment think that I am claiming perfection for School 2 as that would be frankly naive but the difference is extraordinary when compared to School 1. With Ofsted looming, the message from School 1 was 'do more on your displays, marking and make your lessons jazzy'. Staff were required to have Ofsted ready lessons for the moment the call came. School 2 was required to carry on with showing what we do on a day to day basis. It was still stressful and exhausting but in no way was it insincere or disingenuous.

In School 1 a weekly staff meeting was billed as ‘CPD’ and staff were asked to create a mood board in their year group teams. All of this the night before a ‘mocksted’ and needless to say said mood boards languished at the back of cupboards proving to have little impact on students or staff development. In School 2, weekly staff meetings are focused on a specific area identified to impact pupil outcomes. For example using the EEF and other sources to identify what effective feedback is and how teachers can use this practically in lessons. This short summation above does not even do justice to the complexity and depth of the CPD delivered in practice over a number of weeks.

My question is: then how can these two schools be graded the same? School 1 had one inspector for 2 days and has a thin report of two pages stating it is 'good'. School 2 had 3 inspectors who were still there at 6.30pm on day 2 meeting with leaders and was also rated 'good'. The two are not comparable. Not comparable by the experience of staff working there, nor by the pupils turning up each day. Not by the parents and community surrounding it or the curriculum delivered.

There is so much dialogue around accountability and Ofsted ‘ramping up inspection rates’ but in essence if we are not using the same rigour we expect teachers to apply in their teaching to the inspections of such are we not just permitting poor practice to continue unchallenged? I, for one, have escaped the tortuous delivery of VAK learning styles needing to be incorporated in every lesson but if Ofsted perceive that as ‘good’ then there must be others still drowning.

Image by fabrikasimf on Freepik.

The Joy of Headship

A guest blog by Sarah Hussey.

Teaching is tough, headship is hard – those of us who work in education know these things to be true! As a head teacher of 12 years and counting I cannot argue with these facts. Yet… I find sheer joy in my job pretty much every day. How you might well ask? By changing the narrative.

In 2019 a heady mix of many factors led me to be signed off work with chronic stress and anxiety for almost 6 months. Impending inspection, results that were far from ideal, managing staff, budget worries, a pretty hideous parental complaint that had me filing harassment charges with the police, and let’s not forget being peri-menopausal (that needs a whole blog in itself!). I was well and truly done and took to my bed where I stayed for some time! Then we had the first lockdown - a truly surreal time for us all.

I am happy and I love my job.

As I write this I am less than a week away from returning to school after our well-deserved break. I still have an impending inspection (God, I wish they would just get it over with), even more budget worries, and concerns about how my families and staff are going to survive the cost of living crisis. These are just a few of the things that are running through my mind. My mind, however, is at least working now as the wonder of HRT has defeated the damned brain fog and anxiety. But, I am looking forward to the new term. I would go as far as saying I am happy and I love my job. How have I got to this position?

The one thing about being mentally at rock bottom is that you can only move up again: I learned the hard way.

The one thing about being mentally at rock bottom is that you can only move up again. I thought for a few months that my passion, the fire that burned in my belly about doing the right thing for all our children had been extinguished and that made me really sad. The truth was that it had become a tiny, flickering ember which grew as I began to feel stronger. Now, I am not advocating that anyone should become this ill because of a job: well-being is vital and should never ever be an afterthought or a bolt on to your curriculum. I learnt this the hard way.

Dig deep and remember your values.

When things get tough you need to dig deep and remember your values – your reason for leading your school. I don’t mean the values that NPQH tell you to have; I mean the things that make the fire in your belly stay alight. I do this job because after 25 years in education I still believe education is a right for all children and can and does open up their world. I believe that a good school is a place where children, their families and your staff feel that they belong. The core of a good school is not necessarily zero-tolerance uniform/behaviour policies etc. It is relationships. Without these, progress will never be made.

Change the narrative – flip that switch.

I know it is tough and I know there are days when you would rather be doing anything but running another parent’s session about phonics or internet safety, but if you try to change the narrative, flip that switch in your head, it can and will make a difference.

What a privilege it is to be in this position.

When I complain about being all things to everyone - teacher, mental health worker, social worker, counsellor - I remind myself what a privilege it is to be in this position. We cannot change the lives of all our families, but we can go some way to helping them. Sometimes just listening to them is all that is necessary. Our support can lead to a family leaving an unsafe home and changing their own narratives. How wonderful that we can have a hand in creating excellent teachers, either being a part of their training or their ECT years. That is the future of teaching in our hands. Don’t you get an immense feeling of satisfaction when a learning support assistant grows in confidence, learns from your mentoring and the CPD you provide, and goes on to become cracking teacher? How amazing is it that we can encourage the curiosity of our children, that we can teach them to read, which opens up the world around them. I love it when ex-pupils come back to tell us what they have achieved and tell us about the part we played in that – priceless. In what other job can you leave the boring paperwork on your desk and go and find thirty four-year-olds to play with. Their energy and view of life is really inspirational!

I allow my staff to attend their children’s first day at school, their school plays and concerts and their graduations – they are special memories to be treasured.

Headship is a hard job. One of the ways to do it well is to learn not to listen. Don’t go ignoring everyone, but learn to choose the information that you think is important. Don’t be tempted to try every new initiative and if someone from your LA comes and tells you how to do something, ask them to show you the evidence it works. Remember no school is the same and your context will be different to others. Do what feels right for your school community. For me, the number one tip is look after your staff! I don’t mean organising meditation sessions or yoga with puppies, I mean creating an atmosphere of trust and support. Listen to them, let them know that you care but that you also care about the children. I started teaching when my daughters were very young. My head teacher would not allow staff time off for anything other than a funeral of your closest relatives. When I left an abusive relationship, I was given half a day to find somewhere for myself, the children, and 2 kittens to live! So, I allow my staff to attend their children’s first day at school, their school plays and concerts and their graduations – they are special memories to be treasured. It is worth it – for the one or two staff that might take the mickey, the rest give you their best every day of the week. They will enjoy working at your school in the environment that you have created.

If you want to do it, you can!

I cannot tell you Headship is the best job in the world (I mean being a cocktail taster on a Caribbean island sounds pretty good!) but I can tell you it is wonderful. It is joyous and I still love it. Don’t be put off by the bad press and those stories that you hear from others in the job. If you want to do it, you can! You can be a good head teacher and have a work life balance – but you have to do it your way and with integrity.

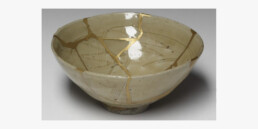

Golden Seams

A guest blog by Aini Butt.

We live in a world where achievement is applauded not the progress itself; beauty standards are set by the finished product and any imperfections are filtered out. So those who are seen as ‘broken’ or ‘wounded’ are told to ‘take your time to heal so you can move on’ or ‘heal and find your old self again.’ Even with the best of intentions when saying something to encourage or motivate others, are our words empowering or reinforcing society’s romanticised vision of healing?

Healing from painful, life-changing experiences is far from romantic and often there is no way back to the ‘old self’, and this is where I question this need to ‘heal and move on.’ It focuses on the past to form a different future; how is this possible when you fail to acknowledge the present?

During a long conversation with a dear friend, we looked back at our similar journeys and revisited our younger innocent selves. As the saying goes, ‘Ignorance is bliss,’ and it sure was until the blessing turned into a curse and became a tool of torture used by those who were supposed to reciprocate the trust and love they were entrusted with. Is this the former self we are told to return to? Is that what ‘finding yourself’ means: to laboriously dig through the rubble of your past to find yourself broken into smithereens under the weight of your dreams and desires, and ‘take time out to heal’ in order to become whole again?

The Japanese art of Kintsugi (golden seams) teaches us the valuable lesson that there is no return to the ‘unbroken’ past; therefore, there is no attempt to hide the breakage either. Instead, lacquer and gold pigment are used to elevate the broken piece. Often, this art is drawn upon to reiterate how our imperfections make us unique and more beautiful. What if this isn’t about the finished piece and the beauty of its shining gold? What if the golden seams are telling the untold story of the creator’s expertise, which reached new heights of craftsmanship with each mended piece? Again, those who will see the finished piece, will congratulate the artist on their creation’s beauty, but the struggles of finding the appropriate tools and resources needed to mend the broken pieces often remains untold.

Similarly, stories of those who are on a journey of self-healing often remain untold. We are so focused on the destination, which we often refer to as ‘finding ourself’, that we fail to recognise that the ‘self’ is not the end outcome in the distant future. It is the work in progress in the here and now- the present. Those who are on a journey of self-healing through self-discovery will know that it requires honesty and courage to recognise that there is no return to the past. They take this as a motivation to continue reflecting however hard this may be without blaming the past for their present.

If I were to go back in time and meet my younger self, I would tell her that her decision to leave the safety of the shore to sail into the unknown was life-changing, and if it weren’t for her determination and resilience, I wouldn’t be where I am today. We are so quick to judge our past decisions and actions by discarding them as our ‘coping mechanisms’. Upon reflection, there have been many habits I adopted to help me with the aftermath of being in an abusive marriage: toxic productivity; extensive workouts and controlling food intake; periods of extreme highs and lows, and maybe some more I still have to uncover. Although these coping mechanisms were unhealthy, I cannot ignore the fact that they got me to where I am today. Instead of blaming myself and living in regret for adopting these habits, I have learnt to accept their use in the past as a way of self-defence.

Acceptance comes from self-love, which wouldn’t have been possible without the promise of loving myself like I would love those who are dear to me. However, this same self-love demands reflection and the recognition for a more compassionate approach as resorting to old habits, thoughts and beliefs will only drag me back to the past. This is the part of healing we find too shameful to share when those around you can’t see your internal storms. The struggles of constantly rephrasing the critical inner voice because silencing its message is not an option anymore. On days when it whispers the worst-case scenarios, you learn to look for the roots of this fear and slowly become more compassionate towards yourself.

Often the hardest mountain to climb is the one when you journey within, where you find fragments of your former self buried under the weight of guilt and shame. Are you able to let your tears flow without shaming yourself or have you restrained yourself behind these bars of strength? If you desire to break free from this self-imposed cage, you will have to sit with the guilt you have harboured and only through the flood of tears will you rephrase the message of your inner voice.

These times of inner turmoil will be the moments where your expertise is further enhanced and your craftsmanship will allow you to mend your pieces with golden seams.

Image from https://art.thewalters.org/detail/10841/bowl-28/