AI, Headship and the “Dirty Feeling”: Towards Conscious Use in Schools. Sam Isaacs, Headteacher

When I was invited to speak to fellow headteachers about AI, my first thought was, “What a brilliant chance to learn out loud, hopefully supporting my peers from a fairly prestigious platform provided by the local authority.” My second was, “What on earth do people think I am - an AI expert? Why me – what have I been saying about my AI use? Do they think I’m a lazy, shortcut headteacher?” I’m not. I’m a curious practitioner who’s made plenty of mistakes, noticed what helps, and tried to be honest about what doesn’t. That’s the spirit I’m bringing here too: no hype, no doom - just what’s proving useful, what’s uncomfortable, and how I feel I can lead with integrity and care with AI as a tool. An AI Headteacher? An AI-enhanced Headteacher? Perhaps the latter – let me tell you why.

Confession first

Earlier this year, I found myself drafting a eulogy. In that tender, human space, a tiny voice whispered, “AI could help you say this well.” That was a wake-up call. I realised AI had started to reshape my instincts. Every little AI win I experienced professionally for the preceding months had given me a dopamine nudge: this saved time; this sharpened the message; this made me better. Helpful? Yes. But it also left a faintly “dirty” feeling - had I outsourced something essential?

I don’t think we can talk about good AI use in schools without attempting to explore the psychology. If we want our colleagues to adopt tools safely and sustainably, we need to model the internal checks - not just the external rules.

Three questions I now ask every time I touch AI

Over the last year, I’ve codified three questions that help me use AI consciously, not compulsively:

- Will it improve the quality?

- Will it save time (and how will I reinvest that time in people)?

- How will it make me feel about my work? Will I still recognise my voice, values and judgement?

If I can’t answer those clearly, I don’t use it. And even when I do, I never outsource the final judgement.

The three “methods” that have changed staff conversations

To make this practical and to keep us honest with parents and governors, I’ve been framing AI use around three simple methods. They’re not formal policy language; they’re a shared code colleagues can actually remember and use.

- Method 1: Human prompt → AI generates → Human refines

- Great for low-stakes, text-heavy grind: quick procedural updates, quiz questions, tidy minutes from a transcription.

- Upside: huge time-saver.

- Watch-out: it’s where the “dirty feeling” creeps in quickest. Use sparingly. - Method 2: Human first draft/details → AI develops → Human refines

- Good for weightier comms, policy summaries, or model texts where your thinking is already on the page.

- Upside: raises quality and consistency.

- Watch-out: don’t let AI smooth off all the humanity. - Method 3: Human draft → AI critiques → Human improves

- My default for anything high-stakes: plans, change initiatives, safeguarding comms, HR docs.

- Upside: keeps authorship, improves rigour, surfaces blind spots, critiques against key policies/guidance.

- Watch-out: takes discipline (and a bit more time) — but it’s worth it.

When I score (out of 5, with 3 being neutral) each method against the three questions (quality, time, feeling), Method 3 wins for leadership tasks (with an overall score of 12.5 out of 15), Method 2 has a strong place (12 out of 15), and Method 1 is less helpful, but has its place (11 out of 15). And importantly, I noticed all three methods had a net positive (>9) overall score… I’ve found this to be a helpful reflection task for all colleagues to consider.

What AI is genuinely good at in leadership

- Taming the text-heavy grind. Drafting first passes of letters, newsletters, governor papers, or turning a messy transcript into clean minutes.

- Policy sense-checks. Cross-referencing school docs against statutory guidance to spot gaps before they become headaches.

- Safeguarding micro-training. Bite-sized mini quizzes and explanations, grounded in KCSIE language to drip-feed reminders in briefings.

- Crisis triage. Anonymised scenarios to map next steps against policy and local processes before you pick up the phone.

Used well, this has meant more presence with pupils and staff, sharper communication, and greater confidence that we’re compliant and compassionate.

The bit no one warned me about: personality and “AI pull”

If you’ve ever done Insights or DISC, you’ll know we all bring different energy preferences. Mine isn’t naturally “blue”—methodical, painstaking, detail-first. Guess what AI is scarily good at? Blue tasks. I feel that makes someone like me more susceptible to overuse. Colleagues who are naturally blue often prove to be our healthy sceptics, and I’m grateful for them. Without any data or research that I can find, I am curious as to how building this into training helps teams see why reactions to AI differ and why mixed-energy planning is a strength, not a clash.

Guardrails that protect people (and trust)

I’ve come to believe that ethics plus compliance is the only sustainable foundation:

- Data minimisation by design. No personal/identifiable data in public models. If in doubt, redact or don’t use.

- Use tools that don’t train on your inputs and allow deletion/incognito. Configure settings accordingly.

- Human authorship and accountability. AI never makes high-stakes decisions about pupils or staff; humans review, edit and sign off.

- Transparency with your community. If parents ask, we can explain not just that we use AI, but how, in plain language, via the three methods.

- Professional learning and oversight. Short, practical staff training focused on accuracy, bias, tone, and emotional impact; light-touch review through your online safety or digital group.

What this looks like in practice (a few real examples)

- Minutes that don’t cost your Sunday. Auto-transcribe, then Method 1 to produce a clean summary you can sanity-check in five minutes.

- Parent comms under pressure. Method 2 to refine tone: clear, kind, and firm, without sanding away your school’s voice.

- Safeguarding drip-feed. Method 1/2 to build one question a week, anchored in current guidance, to keep everyone alert.

- HR and recruitment. Method 3 to critique adverts, role profiles and selection tasks for clarity and fairness; and to spot AI-written personal statements that don’t match the human in the interview (we’ve all seen them, or will do soon).

A note on lesson planning

Tempting as it is to “generate me a full lesson on…” I’m steering staff towards Method 3: “Here’s my plan - critique it against X outcomes and Y guidance.” Ownership matters. So does professional growth. AI can be a coach; it shouldn’t be your substitute teacher.

If you’re starting out, try this

- Pick one leadership task this week and run it through Method 3. Notice what improves, and what still needs you.

- Ask the three questions before you touch a model. If you can’t answer them positively, don’t use it.

- Make a 1-page “Ways We Use AI Here.” Use the three methods as your spine. Share it with staff and governors; be ready to share it with parents.

- Pair opposites. Match a meticulous, detail-focused colleague with a big-picture thinker. Compare outcomes with and without AI.

Back to school: Wellbeing insights for educators, students and families for the academic year ahead

10 Ideas for Wellbeing in the New School Year

As the new academic year begins, the excitement of fresh starts often collides with the pressure of new timetables, commitments, and expectations. Whether you are a teacher, a member of support staff, a student, or a parent, the demands can feel endless.

Dr Emma Kell, teacher and staff wellbeing specialist, and counselling psychologist Lina Paumgarten, who has worked in international schools for over 20 years, recently came together to share 10 simple, powerful ideas for looking after ourselves and one another as the school year unfolds.

Emma’s Top 5 Tips for Staff

- Plan something to look forward to.

Put a date in your diary that’s just for you — a walk by the river, coffee with a friend, an afternoon tea. It doesn’t need to be extravagant, but it should bring joy and remind you that life exists beyond school. - Know your glass balls.

We are all juggling. Some balls are plastic — they can drop without major consequence. Others are glass — your health, your relationships, safeguarding, professional growth. Know what your glass balls are and keep them in the air. - Accept the job is never done.

Teaching is infinite. If you’ve read Oliver Burkeman’s 4000 Weeks, you’ll know the power of accepting that you’ll never get everything done. Focus on what truly matters and make peace with the rest. - Build your team.

Who are your tent poles — the people you lean on in times of need or inspiration? They might be colleagues, friends, or mentors. Know who they are and use them. - Focus on what you can control.

Stephen Covey reminds us to centre our energy on what we can influence. With so much happening in schools and beyond, it’s easy to become consumed by what’s outside our control. Anchor yourself in what you can do.

Lina’s Top 5 Tips for Students (and Families)

- Find a trusted adult.

Every young person needs at least one adult in school they can go to — someone who understands their world. This might be a teacher, mentor, or coach, and it doesn’t need to be the same person for everything. - Create a sustainable routine.

Don’t sprint through the first fortnight of term and collapse by October. Establish a rhythm you can maintain, with planned breaks and genuine downtime — some of it away from screens. - Value rest.

In South America, the word sobremesa captures the joy of lingering at the table after a meal, talking for hours. Build those unhurried, screen-free moments into your life. - Complete is better than perfect.

Perfectionism keeps us stuck. Define what “complete” means for you and allow yourself to move forward instead of aiming for flawless. - Choose kindness.

School life isn’t free of harshness or bullying, but each of us can make the environment a little better. Start with yourself — be kinder to yourself and extend that kindness to others.

The Overlap

What became clear in our conversation is how much these lists overlap. Staff tips apply beautifully to students, and student tips are just as valuable for staff. That leaves us with 10 tips for everyone in a school community; practical, simple, and low-cost.

At their heart is a reminder that we are human beings, not human doings. Intentionally making time to rest, connect, and focus on what matters most is the foundation of a healthier, happier school year.

Final Thoughts

We wish all students, staff, and families the very best as you step into the new term. Take these tips, adapt them to your own context, and share them with those around you.

And if you have wellbeing strategies of your own, we’d love to hear them — share them in the comments and keep the conversation going.

From Dr Emma Kell and Lina Paumgarten — sending you a big high five for the year ahead!

Attendance: A Vicious Circle

A guest blog by Sarah Garner, Deputy CEO, Unity Schools Partnership.

In many organisations, particularly in the educational sector, a vicious circle often emerges, linking attendance, outcomes, reputation, and funding. This self-perpetuating cycle can have detrimental effects on the sustainability and success of an organisation. Understanding this cycle is crucial for stakeholders to develop strategies to break free from its negative impact.

Attendance

Attendance is a fundamental component of any educational system, as it directly influences students' engagement and learning experiences. Low attendance rates can lead to significant gaps in knowledge and skills, impeding students' abilities to perform well academically. Furthermore, chronic absenteeism is often indicative of broader systemic issues within the institution, such as lack of support, unengaging curriculum, or inadequate resources.

Outcomes

The outcomes of a school, encompassing both academic results and broader student development, are highly dependent on attendance. Poor attendance typically results in lower academic performance, which in turn affects results in internal and national exams. These subpar outcomes reflect negatively on the school and can hinder its ability to attract and retain students.

Reputation

A school’s reputation is built on its ability to deliver positive outcomes. When students do not perform well, either academically or in extra-curricular or enrichment activities, it tarnishes the school’s image. Prospective students and their families will reflect on the school's reputation when making decisions about enrolment. A damaged reputation can lead to decreased admissions, exacerbating the issues of low attendance and poor outcomes.

Funding

Funding is critical for the operation and improvement of schools. Public funding sources are indirectly linked to a school’s reputation and performance when allocating resources through the number of students taking a place at the school. Declining attendance, outcomes, and reputation therefore will result in reduced funding, which further limits the school’s ability to address the root causes of its problems. This reduction in resources can lead to cuts in staff, programs, resource and support services, creating an environment that perpetuates the vicious circle.

Breaking the Vicious Circle

To break free from this detrimental cycle, schools must adopt a multifaceted approach that addresses each component of the circle. Strategies may include:

- Implementing initiatives to improve student (and staff) engagement and attendance, such as personalised learning plans and targeted support services.

- Enhancing academic outcomes through curriculum reform and pedagogy, professional development for educators, and increased access to learning resources.

- Investing in marketing and community outreach to rebuild and maintain a positive reputation.

- Investment in staff, happy staff equals happy (attending) children, staff wellbeing, workload, professional development, staff incentives and benefits schemes.

- Financing of capital programmes to enhance and improve learning areas, keeping children engaged, inspired, warm and safe.

- Advocating for stable and adequate funding from governmental and Local Authorities to support long-term institutional improvements particularly with regards to SEND.

By addressing the interconnected aspects of attendance, outcomes, reputation, and funding, institutions can create a positive feedback loop that fosters growth and success, ultimately breaking the vicious circle.

A SCITT Survival Story: What I Learned About Teacher Training and Myself

An anonymous guest blog.

Before You Read My Story…

I’m now thriving as an Early Career Teacher (ECT), with a fantastic mentor and students who are engaged and motivated. I’m finally in a place where I feel like I can do what I came into teaching to do. But the journey to get here was far from smooth; at times, it nearly broke me. I’m sharing my story because teacher training, especially SCITT (School Centred Initial Teacher Training) programmes, need to do more to support the wide range of people they recruit. The system is not currently set up for everyone to succeed, especially those who are neurodivergent or facing personal challenges.

Why I Retrained to Teach

Before training to teach in secondary schools, I worked in higher education, supporting students on a university course. I loved the subject and the students, but I noticed something worrying: many lacked creative confidence. They were hesitant and unsure of themselves; it felt like something had been lost along the way in their education. I wanted to intervene earlier, to help nurture that spark before it dimmed.

Then came Brexit, followed by COVID. The university closed, and my job disappeared. With no clear next step, I looked towards teaching in schools. It felt like a meaningful way to use my skills, with more financial stability than freelance work. Teachers in my subject were in short supply, so retraining seemed logical and hopeful, a way to make a difference earlier in students' journeys.

I applied to both a university-led PGCE and a SCITT, ultimately choosing the SCITT route for its practical focus. I had no doubts about my ability to teach, but I knew behaviour management would be a steep learning curve. I’d only ever worked with adults who had chosen to be there. Teenagers, I suspected, would be an entirely different story.

The SCITT Setup and My State of Mind

The SCITT programme began with a large intake of both primary and secondary trainees. We all received the same general training, often in noisy, crowded rooms that felt overwhelming. I found it hard to concentrate, hard to settle, and hard to be present in that space.

On top of the sensory overload, I was grieving. The previous year, I’d lost family members and close friends. I’d hoped that throwing myself into something structured would help, but I underestimated how fragile I still was. I flagged to the SCITT team early on that I might need a bit of space sometimes, not major adjustments, just understanding. I explained that I was a self-directed learner, and that I’d be more focused if I could do some of the more general training independently at home. But I was told attendance was compulsory. Eventually, I was allowed to leave the room when overwhelmed, but even that felt like a small battle. Simply walking out past a large group felt exposing and stressful.

Around this time, someone gently suggested I might be autistic. I started reading, reflecting, and pursuing a referral. The signs were all there, the shutdowns, the sensory challenges, the exhaustion. It made sense of so many things I had never been able to explain.

A Lack of Agency and Support

The SCITT programme was well-meaning. They seemed genuinely caring and wanted to support trainees. However, that care often felt like it was coming from a place of good intentions, but not always from an understanding of what each individual trainee needed. They listened to my concerns, but only on a surface level, responding in ways that didn’t really address my needs or adjust to my specific situation.

When I explained that I needed space or that I worked best independently, the responses were more about "following the programme" than accommodating different learning styles or personal circumstances. There was little recognition that trainees might be juggling complex personal histories or neurodivergent traits that required a more tailored approach. I felt as though I was constantly battling to have my voice heard, but not really listened to.

It would have made all the difference if the SCITT had worked with me, rather than around me. Respecting trainees as adults, neurodivergent or not, should be the baseline. Only at the end of my training, when I had finally made clear how critical it was for my well-being, did the SCITT truly listen and adjust.

Two Very Different Placements

In my first long placement I had a mentor who trusted me, a quiet space to retreat to, and a school that believed in growth rather than perfection. I thrived. I was told I was nearly ready to qualify. My confidence began to rebuild.

Then came the second placement.

The atmosphere was completely different. Expectations were sky-high, support was minimal, and feedback felt never-ending. I was asked to write an entire curriculum from scratch, with no guidance and no scheme of work. Observations were constant. My self-esteem plummeted. When I raised concerns, they were dismissed. Eventually, the SCITT intervened and advised the school to focus on one target at a time. While that advice helped, the damage had already been done.

Recovery, Qualification, and Diagnosis

After a poor final observation, I finally saw the truth. I wasn’t failing; the system was failing me. I realised I was never going to pass the QTS in that school, so I returned to the first school, where I felt safe and supported. I completed my QTS there and passed with flying colours. The difference? I was trusted, and I was heard. Since then, I’ve been diagnosed with autism and advised to be screened for ADHD. That clarity has helped me embrace who I am, as a person and as a teacher. It’s made me stronger.

Looking Back: What Needs to Change in Teacher Training

Reflecting on my journey, I realize how much potential is lost when teacher training doesn't truly understand or respect the diversity of its trainees. Well-meaning as they were, the SCITT team never truly listened until it was nearly too late. Too many barriers remained that could have been easily overcome with a more empathetic and flexible approach. SCITTs can improve by offering more flexible learning options, such as self-paced training and remote learning for those who need it. They should provide better awareness and understanding of neurodiversity, ensuring that mentors are trained to recognize and support individual needs. Communication should be clearer, with regular check-ins and a culture where trainees feel heard and supported.

Mentorship should be proactive, matching trainees with mentors who understand their unique challenges. SCITTs should also create inclusive environments where differences are celebrated, offering mental health resources and well-being check-ins. Post-training support and a more holistic approach to assessment, considering well-being alongside performance, would also help. Lastly, connecting trainees with external networks for additional support can provide crucial resources for those facing challenges.

These changes would ensure that SCITTs are better equipped to support all trainees, leading to a more inclusive and effective teacher training process.

I hope my experience serves as a reminder that teacher training programmes must create space for diversity, not just in students, but in the teachers who are being trained. Everyone has a story, and each story deserves to be heard.

All of this has made me a better teacher, one who advocates for students who don’t feel heard, who lack agency, and who may be struggling in ways that are often overlooked. I’m committed to ensuring that every voice is valued and every learner is supported in the way they need to thrive.

Takeaways and Advice for Trainees

- Advocate for yourself: Don’t be afraid to communicate your needs early on. Whether it’s sensory sensitivities, workload concerns, or needing extra support, speaking up can help ensure you get the help you need to succeed.

- Understand that it's okay to struggle: Teacher training is tough, and it’s normal to face challenges. Recognize that struggles don't mean you're failing — they're part of the learning process. Be kind to yourself when things don’t go as planned.

- Look for a supportive environment: Trust your instincts about the schools and mentors you work with. Seek out environments that make you feel safe, valued, and respected, and don't hesitate to request a change if things don’t feel right.

- Set boundaries (even if it’s tough): During your PGCE or QTS, it’s hard to set boundaries, but remember it’s temporary. While it may not always be possible to take a step back, try to find small ways to recharge when you can. Burnout is real, so focus on manageable steps to reduce stress and prioritize self-care when possible. This phase will pass.

- Seek external support: If your training programme isn’t providing the support you need, don’t hesitate to reach out to external organizations, mentors, or networks. Asking for help is a sign of strength, not weakness. I highly recommend Now Teach, an organization that specializes in supporting career changers and those entering teaching later in life. Their guidance and support were invaluable to me.

- Trust your growth: You might not feel "ready" at every stage, and that’s okay. Trust that you're developing as a teacher, even if it doesn’t always feel like it. Progress takes time, and you're building a foundation that will serve you throughout your career.

Embracing Pragmatism in Teaching, Coaching, Wellbeing… and Life

When I became a doctoral researcher 14 years ago, one of the first steps to examine my ontological and epistemological assumptions. Sorry, what now? The big words were initially utterly overwhelming as well as being entirely unfamiliar, as well as a little intriguing... Was I an interpretivist? A phenomenologist? An existentialist?? Who knew. All I knew was that I was a sleep-deprived newish Mum who’d embarked on this crazy academic journey alongside a middle-leadership role, and my imposter syndrome was in full carnival mode. I was in the midst of a (quite literal) identity crisis when I stumbled, to my relief, against the academic concept of pragmatism; my favourite kind of academic concept – one founded in common-sense. To this day, I unashamedly describe myself in life and work as a pragmatist.

What does that mean in practice? It means I don’t align myself with the fiercely fighting education camps on social media. These days, I observe such debates with a wry amusement. Let’s take children and toilets. There’s a time to say, ‘if you’re still desperate for the toilet in five minutes, let me know. Otherwise, get on with your work’ and a time to let that child go – now. It’s about knowing the child.

Pragmatists do what works, and that’s what I love about it. Pragmatism is about caring less about the things that matter less (like a messy house, in my case) and channelling attention and emotional energy to the things that matter most.

I'm open to debate and discussion, and I have no issue with people challenging me or the ideas I share. Some of my best ideas come from being challenged. For example, I once asked a group of policymakers from Central Africa and Eastern Europe about staff wellbeing in their schools. One of them politely but firmly said, "I think first you should ask us why should we care?" That powerful question is one I now often open my sessions with.

My identity as a teacher, researcher, writer, and speaker is closely tied to being a pragmatist. This means I listen—really listen - using my coaching skills to those who come my way. I constantly collect gems of wisdom and share them with others in education to enable as many people as possible to be the best versions of themselves.

A Pragmatist's Approach to Wellbeing

Wellbeing differs for each of us. I talk with a mix of amusement and frustration about how I can’t bear to be ignored when I greet someone in a school corridor or give an instruction to a class. But someone once said, "That person might not have even seen you." Their head might have been elsewhere – and it made me review my approach and remember that it's very rarely about me… I also refer to my rather casual approach to possessions and my tendency, if I've seen a new glossy stapler on someone's desk, to nip in and borrow it, then forget I've done so.

Pragmatism is an antidote to the FOMO many of us feel. ‘You do you,’ as my teenagers would say. Carve your path and make your way forward. Pragmatism also means that very few approaches are wholly right or wholly wrong. I'm wary of silver bullets; the allegedly brilliant ‘solutions’ to all that is wrong in education that some brandish as if they’re the only ones to have found the Holy Grail.

Small Changes for Big Impact

When I work with my coachees and wellbeing delegates, on mindsets and beliefs that are holding them back, like perfectionism or an urge to apologise, it’s not about changing people. It’s about asking, "How has this belief benefitted me so far, and why is now the time to tweak my approach?" All the work I do is about small changes, not radical transformations.

Ultimately, what do you want your legacy to be? What works for you and your self-care? Is it long lie-ins, reality TV, walks with the dog, or a spa day? Whatever works for you, as long as it doesn’t hurt anyone else (as a wise person said when I first became a sleep-deprived parent), that’s absolutely fine. We all need to feel appreciated, whether it's through bells, whistles and certificates or a quiet word, but be clear – and talk about – what works for you.

Pragmatism is also about being philosophical when things don’t work. The approach I take to all of my work is 'iterative' (another lovely common-sensical academic term. You keep with your approach until you find something that works, and when that stops working, you find another approach. Or, put more bluntly, you keep making it up as you go along..

In education, it's about doing the small things that allow you to live a happy, fulfilled, productive, and meaningful life. That's what I aim to help others achieve.

If you’d like to talk more about my approach to wellbeing, effectiveness, and stakeholder engagement, please get in touch.

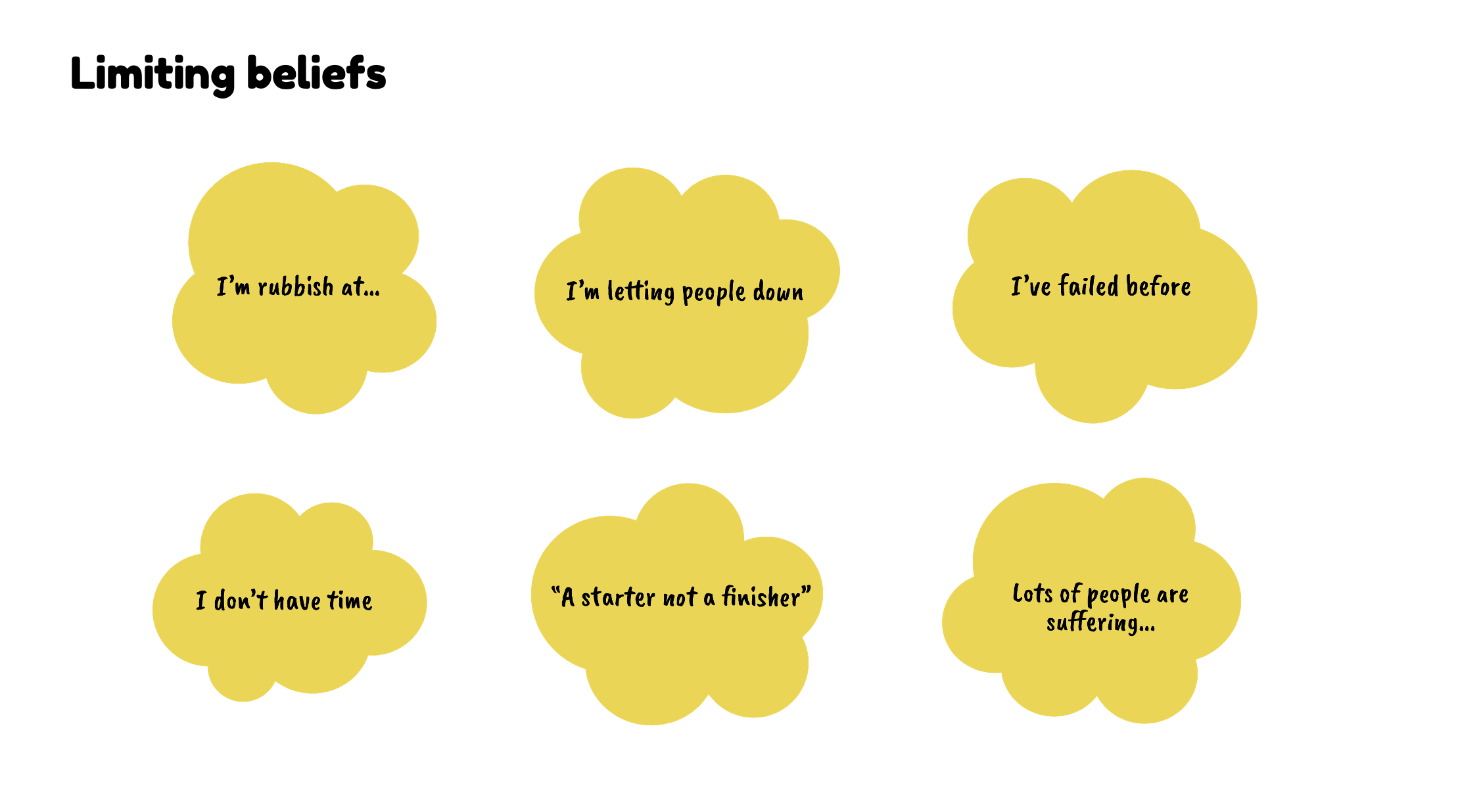

Overcoming Limiting Beliefs: Embracing New Perspectives for Personal and Professional Growth

We all have beliefs about ourselves that shape our thoughts, actions, and ultimately, our careers and lives. Some of these beliefs serve us well, while others hold us back from reaching our full potential. These restrictive thoughts are what we call "limiting beliefs." Today, let's explore how to identify and overcome these beliefs to foster personal growth and achievement, drawing inspiration from examples shared by Mary Myatt in interview with me, Dr Emma Kell.

Understanding Limiting Beliefs

Limiting beliefs are deeply ingrained thoughts or perceptions we hold about ourselves, others, or the world around us. They often form early in life based on our experiences and environment. We may be coming to realise that these beliefs about ourselves have become outdated and started to hinder our progress and happiness.

It’s crucial to understand that these beliefs are not inherently good or bad. They're simply perspectives we've adopted over time. The key is recognising when these beliefs no longer serve us and finding the courage to challenge and reframe them.

Examples of Limiting Beliefs

Here are some anonymised examples cited by recent coachees:

And here are a couple Mary and I discussed:

And here are a couple Mary and I discussed:

1. The Productivity Trap

I share a common limiting belief: the idea that to be successful, we must be busy all the time. This belief often manifests as "performative busyness" - the need to appear constantly occupied and overwhelmed.

I personally held this belief for years, thinking that as a business owner and teacher, I needed to always be visibly, sometimes performatively, busy. This led to multitasking, which ironically decreased my overall productivity and effectiveness. By challenging this belief, I learned that focused work and intentional rest are far more valuable than constant activity. I strive to embrace the ‘one thing at a time’ mantra.

2. The Suffering Comparison

Another limiting belief Mary discusses is the idea that one's pain or struggles are invalid because "others have it worse." This belief can be particularly challenging for those dealing with illness or mental health issues.

Mary gives an example of someone battling cancer who feels they don't have the right to complain or feel anxious because "other people are suffering more." This comparison minimizes personal experiences and can prevent seeking necessary support and care.

Reframing Limiting Beliefs

This coaching approach involves several steps to overcome limiting beliefs:

- Awareness: Recognise the belief and its impact on your life.

- Questioning: Challenge the validity of the belief. Is it based on fact or assumption?

- Reframing: Create a new, empowering belief that better serves your goals and wellbeing.

- Action: Act in accordance with your new belief to reinforce it.

Let's apply this to the examples provided:

Productivity Belief:

- Old belief: "I must be busy all the time to be successful."

- Reframed belief: "My success is measured by the value I create, not by how busy I appear."

Suffering Comparison Belief:

- Old belief: "I don't have the right to feel bad because others have it worse."

- Reframed belief: "My feelings are valid, and acknowledging them allows me to address my needs and practice self-compassion."

It’s essential to approach this process with self-compassion. Change takes time, and it's normal to sometimes fall back into old thought patterns. The goal is progress, not perfection.

Moreover, Mary points out that reframing our beliefs often leads to a more balanced perspective. In the case of the suffering comparison, acknowledging our own pain doesn't diminish the struggles of others. Instead, it allows us to cultivate genuine empathy - both for ourselves and for others.

As this coaching demonstrates, identifying and challenging limiting beliefs is a powerful step towards personal growth and fulfilment. By questioning the thoughts that hold us back and reframing them in a more empowering light, we open ourselves up to new possibilities and experiences.

Remember, this is a journey, and it's okay to take it one step at a time. Whether you're tackling beliefs about productivity, self-worth, or any other aspect of your life, approach the process with patience and kindness towards yourself. As you release these limiting beliefs, you may find yourself capable of achievements you never thought possible.

What limiting beliefs are you ready to challenge and reframe in your own life?

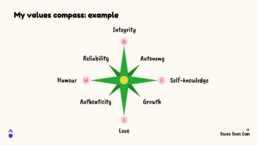

The Values Compass: A Guide to Personal and Professional Alignment

In our journey through our careers and lives, we often find ourselves at crossroads, facing decisions that shape our personal and professional paths. One powerful tool that I've developed in navigating these choices is what I call the "Values Compass." This concept has been a guiding light for me and many of those I've worked with, helping us align our actions with our core beliefs and expectations. It is one of the many powerful tools I share in the Being Your Best, Doing Your Best course that I've developed for Huh Academy: https://huhacademy.com/courses/18-byb-dyb-cohort-24-25/

You can hear me talk through this activity and other activities from the course with Mary Myatt for FREE here: https://huhacademy.com/intro-webinar/18-byb-dyb/

What is the Values Compass?

The Values Compass is a personal collection of principles that guide your decisions, fuel your passions, and define what you stand for. It's not just about what you believe in, but also what you expect from others and the organisations around you.

Why is it Important?

When we live and work in environments that reflect our values, we thrive. Conversely, when we find ourselves in situations that challenge our moral compass, it can significantly impair our wellbeing – mentally and sometimes even physically. I've experienced this firsthand, and it's why I'm passionate about sharing this concept.

Creating Your Own Values Compass

Here's how you can create your own Values Compass. Use this list of values (generated from my work with educators at all levels over the last five years) to help you - this list isn't exhaustive, so feel free to suggest your own values.

- List Your Top Eight Values: Think about the principles that guide you most strongly. You can choose a specific context if you like – as a parent, educator, professional, etc. You don't have to list them in any particular order at this stage.

- Identify Your North Star: Draw a basic compass (or print this one). If you could only choose one value, what would it be? This becomes your "North" on your compass. Write it above the 'north' point. For me, it's integrity. Nothing hurts more than having my integrity questioned or when someone makes unfounded assumptions about me.

- Define Your South: This is your second strongest value. For instance, I might choose reliability. It's something I've had to work on, but it means a lot to me, and I expect it from others too.

- Choose Your East and West: These could be contrasting values that don't necessarily sit comfortably together. For example, I might put empathy in the East because I often experience intense empathyfor others. In the West, I might place excellence, as I always strive to do my best.

- Fill in the Remaining Directions: Place your other values in the remaining spots on your compass, considering how they relate to each other. Here's an example:

Applying Your Values Compass

Once you've created your Values Compass, use it as a tool for reflection and decision-making:

- Hold it up against challenging situations you face. What does that feeling of frustration or dissonance tell you about your values?

- Use it to analyze situations where you've thrived or had the impact you wanted.

- Share it with your team or family to foster understanding and alignment.

Remember, there's no wrong answer. Your Values Compass is unique to you and can evolve over time.

Creating and using a Values Compass has been transformative for me, both personally and professionally. It's a simple yet powerful tool that can help you make decisions that align with your core beliefs, foster better relationships, and ultimately lead a more fulfilling life. I encourage you to take the time to create your own Values Compass – you might be surprised at what you discover about yourself in the process.

If you're happy to share your compass on social media or in the comments, please do! We'd love to see it. And if you'd like more where that came from, do join me and Mary Myatt on our brand new course with powerful coaching tools for leaders at all levels: https://huhacademy.com/courses/18-byb-dyb-cohort-24-25/

Take our quiz to find out how it might benefit you: https://mary-qm81cvoh.scoreapp.com

Removing OFSTED Single-Word Judgements. What Is the Big Deal?

A guest blog by Sarah Hussey.

For a brief time, this morning (2nd September), the news headlines about the immediate changes to OFSTED filled me with optimism. That is until I read some of the comments about this on a range of social media platforms. Particularly, a comment on the Facebook page for ‘This Morning ‘, which alluded to how easy the job of a teacher is and that inspectors should just turn up without giving any notice – blah blah blah – we have heard it all before!

Of course, initially I thought the negativity was not from anyone in the profession and then I saw the headline in The Telegraph – ‘Labour’s Ofsted system puts feelings above facts, says Birbalsingh.’ I know, I know these things are said to antagonise, but I couldn’t stop myself having a look at the X account of said ‘strictest headteacher in Britain’ where she makes her feelings very clear about the steps Labour are taking. She is very clear that the report card, even though we do not know what it will look like, will NOT give more clarity to parents and states that abolishing judgements because of leaders ‘feeling bad’ is a nod in the wrong direction. And that is why I need to explain why it is such a big deal and why the feelings of school leaders, school staff and communities are not to be belittled.

I have worked in the education sector for 30 years, starting as a midday supervisor in the early 1990s and becoming a head teacher in 2010 and now a coach, trainer and consultant. In all of those years OFSTED have worked with many different frameworks but have always used the one-word judgements. In September 2010, I secured the headship of a one form entry primary school, after teaching in a much larger school in various roles for 10 years. It was my first headship and my first headship interview – I genuinely did not believe that I would be appointed when I applied and thought it would be good interview practice. The school had already put the job out to advert twice and not appointed but there I was excited, ambitious and ready to make a difference! The school was rated as outstanding, this happened 3 years before my arrival and in the June before I started OFSTED sent a one page letter to parents saying that it was still outstanding – to this day I have no idea how they arrived at that decision. Inspectors would not cross the threshold of the school again until March 2015 (a wait of 8 years). So, here we are my very first, but not last, experience of how the one-word judgement was not a reliable or realistic picture of how well that school was actually performing. From the first day of my 13-year role, it was abundantly clear that the school was not outstanding – in fact it was far from it. However, if you are told that you are that good for long enough you run the risk of becoming: a) complacent or b) arrogant – or even worse both! In my earlier role, I was used to attending child protection conferences for vulnerable families and working with other professionals, here the safeguarding records were a notebook in an unlocked drawer! This changed overnight, in case you were wondering? If you wanted your child to sing all day, invite their granny for lunch and be able to enjoy lots of fun activities then this was the school for you and it was a very popular school, in fact it was oversubscribed every year. The school of choice in the local area. The reality was outdated teaching methods and learning that just did not happen quickly enough or deeply enough. I don’t know if I managed to hide my shock at the first governors meeting that I attended as it was not very different to the parish council meetings in the Vicar of Dibley! Nobody wanted to change how things were and as long as it had the outstanding badge very few people (apart from that new head teacher) could see any reason why they should. As a new head teacher, I thought that I would get some support from the LA, but of course we weren’t considered to be a high support school, so there was no funding at all.

Now, I know that some of what I have just said sounds very harsh, and I might appear to be a bit like the strictest head in Britain – I really am not! In fact, even quite recently a family moved their child to my school as they had heard that I didn’t really care about year 6 SATS. I admit this may not be the best advert for high standards in a school, but the point they were making, and they were right, is that I have always maintained that the summative assessments primary school pupils have to do are only a very small part of the picture of their success at school.

Let’s fast forward to March 2015 and the return of the inspectors, a 2-day full and rigorous process and the outcome was ... requires improvement. My reaction to this report was that I was incredibly proud of what it said about the school I had been leading for 5 years. Did I agree with the one (two) word judgment? We were good in some areas and the word outstanding was used when describing our pastoral care, but that wasn’t the overall ruling – even then, it seemed like a very strange system. Despite the new, not so shiny rating, the report was 10 pages of insightful information, and it described an effective and ambitious school. The community did not fall apart, in fact they supported the changes that needed to be made, and the school thrived.

Example number 2 of how the one-word judgment if taken at face value and not followed up with further investigations was unreliable and unrealistic. Can you see an argument for a better system emerging – one with a report card that gives parents more detail perhaps?

If you had believed the first judgment of outstanding or the second of requires improvement you would have been wrong on both counts!

Over the next few years, the landscape and rhetoric around OFSTED certainly changed dramatically. There were so many changes to the framework that the goal posts were moved right off the pitch! One of these changes was the introduction of the dreaded ‘Deep Dives’ which were unworkable in primary schools, particularly in smaller ones where some members of staff would be responsible for 2 or more subjects across the school. Members of staff on my team were kept awake worrying about the interviews that they would be having with inspectors about how their subjects were taught over 7 year groups, despite having very little leadership time in reality to do their role! A prime example of trying to make a secondary school model fit all schools.

So onward to 2020 and we were ‘in the window’ again and it felt very different to the other occasions. In the Autumn term of 2022, colleague heads of neighbouring schools had their ‘good badges’ removed and replaced with requires improvement and in conversation told me about the attitudes of the inspectors and their lack of empathy and refusal to listen to evidence that school leaders had to share with them. Heads handed their notice in, and governors started to look at joining MATs. The stress levels of anyone working in schools went through the roof and of course local authorities put more pressure on them as they needed school to stay ‘good’. Teachers were under so much pressure to ensure that the OFSTED needed to see ‘good’ in everything that was done – we didn’t stop to wonder whether one word could possibly describe everything that a school does for its community and beyond. There were so many things that were said to happen if you had a requires improvement or inadequate label:

- You could be slapped with an academy conversion order.

- Your school would be out of favour with parents – fewer children means less money.

- You could find it difficult to appoint new staff as they felt the pressure would be too much for them.

- Some providers would not allow you to have student teachers training in the school.

And the list goes on – how on earth were these schools supposed to improve?

Ironically both Ruth Perry and I had our last OFSTED inspections on the 14th and 15th of November 2022. In a fair and open system both schools should have had the same experience and the same outcomes – yet one head teacher lost her life and the other had to leave her role after becoming so ill that they could not continue.

As I said at the beginning, the reactions this week about the plans to remove this one-word judgment have really got me thinking. The changes are not about the government paying too much attention to school leaders feeling a bit bad – but about the utterly devastating damage that constant stress can do to school communities, individual human beings and their loved ones. You should never be seen as collateral damage to the profession! School leaders and their staff often function in a never-ending cycle of stress under a constant fear of not doing or being good enough. It is crippling to the human body and mind to live in a constant state of fight, flight or freeze – the cycle must be closed.

This is why these changes are a big deal – they will make a massive difference to the profession and the humans that work within it. Sometimes commentators like the ones on X and other platforms actually forget that is what we are – human.

I am hoping that this is the first step in a process that starts to support a profession that has a life-changing impact on our future citizens. I know that schools are effective and successful when professionals are treated with respect, trusted to do their jobs and held accountable in a fair and honest way. We can create amazing schools by leading with compassion, integrity and emotional intelligence. Believe it or not, feelings are important, human interaction relies on it and schools are full to bursting with humans – so I say it again – removing the one-word judgements is a big deal!

Thank you to Ruth Perry’s sister Julia, family and friends and all the other people with integrity and passion for fighting so hard for this to happen.

Beyond Boundaries: Embracing Co-Parenting with Dad's Co-Pilot

A guest blog by Harry Lock.

As a dad, I've learned firsthand the profound impact our relationships have on our children. It's not just about us; it's about creating a nurturing space where our children can thrive, no matter what life throws our way.

I'm Harry Lock, founder of Dad's Co-Pilot, and I'm on a mission to redefine co-parenting and make things better for families everywhere.

My journey into fatherhood wasn't smooth sailing. At 23, I was hit with the reality of impending fatherhood while dealing with a rocky relationship. The road ahead seemed uncertain, but one thing was clear – I was determined to be there for my child.

Navigating the family court system was tough. It tested my strength and determination. But through it all, I kept my focus on what mattered most – my daughter's well-being. Despite the challenges, I gained a deeper understanding of the importance of effective co-parenting and its impact on our kids. Today, I stand as a dad who's been through it – someone who's emerged from the struggles with a renewed sense of purpose.

My legacy is simple: to create a world where every child grows up in a loving, supportive environment, no matter their parents' circumstances. I know co-parenting isn't easy. There are disagreements, hurtful words and tough decisions. But I've learned the power of changing perspective, setting aside differences and focusing on our children's development.

As a coach and thrive practitioner, I'm here to support dads (and mums) in navigating co-parenting with confidence and grace. Together, let's rewrite the narrative, challenge stereotypes, and create brighter futures for our children.

Join me on this journey as we work towards a world where co-parenting isn't just about us – it's about building a better future for our children, one relationship at a time. Together, we can make a difference.

Grit and Growth: The Joys of Girls' Football

I'm proud of my first non-teaching-related piece in a long time, so re-blogging it here. Originally posted here: https://www.instagram.com/p/C2HZtjfshom/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

If you’d told my 20-something self that I’d spend most weekends through my 40s standing by a football pitch, roasting in the sun or soaked to my toes, I’d have snorted. If you told me that it would bring me, and my family, such joy, I’d have laughed in your face. Our daughter, now 14, is a feisty and fearless goalkeeper, playing in the Junior Premier league, alongside two other teams. It’s been the making of her - and us

Like many parents, we tried to put opportunities our kids’ ways from an early age. At 6, gymnastics came to a shouty end, when she interrupted her routine in her first competition to stop over to the instructor, mid-teddy-bear-roll, to ask for clarification on the next instruction with a ‘WHAT?’ that could be heard across the gymnasium. Tragically, piano lessons quickly became a chore that risked putting her off music for life. She’s never been one to sit on the fence when expressing her opinions. Then someone on the school run asked if we’d considered football, and that’s where it began: Chipperfield Corinthians, a mixed village team of five year olds. What could possibly go wrong…?

Plenty did, though the setbacks were greeted with resilience and humour by parents and players alike.

They used to chase the ball like an angry swarm of bees, clumped together as we shouted ‘other way!’ from the sidelines. After 10-0, we’d stop counting the opposition’s goals. Did it put them off? Did it heck. The coaches (unpaid volunteers - even today, for many) were extraordinary in their patience, encouragement and tough love. Dom, Luke and Stewart deserve a name-check, a decade on.

Cut to age 12, when we received a phone call out of the blue. A parent had seen her play in her school team and knew a JPL team, London Football Talent Centre, looking for a keeper. I didn’t know what JPL stood for, but we grasped the opportunity. This took us straight into a residential tournament and took her, at the time a rather quiet and withdrawn type, into sharing a room with fellow teenagers she’d never met - to this day, one of the biggest acts of bravery I’ve seen. As we played Arsenal on ground the texture of razors from the heat of the sun, the temperature hit 38 degrees. ‘It would be cruel to send them on again’ said the coaches (as we scurried back and forth with water and they collapsed and rose in turn from injuries and heatstroke). ‘We’re carrying on!’ said the girls.

Being the parent of a goalkeeper is uniquely stressful. They’re literally the last line of defence and if they mess up, everyone knows about it. Trust me, we’ve seen the silent tears and the closed bedroom door. What we’ve learned is that these girls look after one another. Don’t get me wrong. The sense of justice is strong and I’m not saying that fruity language doesn’t escape when the opposition breaks the rules of decency. But they’re a team, and they stand - and fall, and break - together. They defy the toxic clichés that abound about teenage girls and some days, when I watch them, in this messed-up world, I feel reassured and optimistic that girls like these will be in charge of our world before long. They’re fast, they’re fearless, they’re strong - inside and out. They inspire me as much if not more when they lose as when they win.

The world is a terrifying place, but for a few hours each week, I get to lose myself, ever the embarrassing parent with the shouty encouragement, on the sidelines of a muddy football pitch . The sidelines don’t care about my to-do list or the stresses of my job. I get to watch these girls sprint and tackle and my daughter pouncelike a cat and dive like a dragon and I feel like the luckiest parent alive.

I’m Emma, and when I’m not a football Mum I teach teenagers and support fellow teachers. If you’re a fellow football parent, do get in touch!